Unusual calm before the storms – looking back at the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season

Preseason predictions suggested a seventh, above average Atlantic hurricane season for 2022. However, with no named storms before June 1 for the first time since 2014, and a cyclone drought between July 2 and September 1, the season ended with near-average number of named storms. Hurricane Ian gave a reminder that it only takes one storm to make the season impactful.

Season of 14 named storms

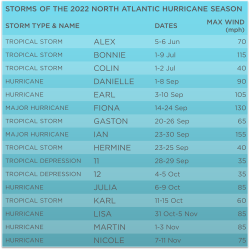

The 2022 hurricane season, which began on June 1 and ended on November 30, saw 14 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 2 major hurricanes. This is very close to the long-term averages of 14 storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes, but less than 2020 and 2021, which were both above-average seasons. A tropical cyclone becomes a named storm once its sustained winds reach 63 km/h (39 mph), a hurricane when sustained winds reach 119 km/h (74 mph), and a major hurricane at 178 km/h (111 mph). Hurricanes Fiona and Ian peaked as major hurricanes, with maximum winds of 215 km/h (130 mph) and 250 km/h (155 mph), respectively.

No storms from July to August

Even though no storms formed before June 1 for the first time since 2014, the early part of the season indicated yet another active year, with three named storms by July 2. Then an unusual calm settled, with no new named storms until September 1. This made 2022 the first year since 1941 with no named storms between July 3 and the end of August, and the first year since 1997 with no named storms in August.

Enter Fiona & Ian

The season picked up in September, with six named storms, including two major Hurricanes: Fiona and Ian. Forming on September 14, Fiona brought heavy rain, damaging winds, and a destructive storm surge when making a landfall on Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Canada. Hurricane Ian developed 10 days later and would be the most impactful storm of the season.

After forming on September 24 over the Caribbean Sea, Hurricane Ian intensified on September 27 and made landfall in western Cuba with winds of 205 km/h (125 mph). From there on Ian rapidly intensified, strengthening to 250 km/h (155 mph) over the Gulf of Mexico, and made landfall in Florida on September 28 with winds of 240 km/h (150 mph). Whilst at peak intensity, significant lightning was present in the eyewall of Ian with the National Lightning Detection Network detecting lightning every three seconds in the storm.

Five more storms developed between October and November, and Hurricane Nicole finished the season by making landfall in Florida on November 10.

Vaisala plays an important part in hurricane reconnaissance

The NOAA Hurricane Hunters and the United States Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunters have combined for hundreds of reconnaissance flight hours into these storms. During these reconnaissance flight the Hurricane Hunters release dropsondes into the storm.

Vaisala-manufactured NCAR Dropsondes* provide atmospheric profiles from aircraft altitude to surface level and measure the storm’s wind speed and direction, air pressure, relative humidity, and air temperature. These data are relayed back to the aircraft and then onto operational meteorologists who analyze the data to better understand the storm. The data are critical for weather forecast models, improving forecast accuracy by approximately 10-15% thus helping to reduce the cone of uncertainty associated with the storm’s trajectory.

In addition to storm reconnaissance and research, dropsondes are also used in various field campaigns to conduct meteorological research and validate other airborne instrumentation.

Why dropsondes are essential to hurricane hunters

Satellites are vital and provide a tremendous amount of information for forecasters. But dropsondes go even further.

Dropsondes collect high resolution atmospheric data and their measurements help in the understanding of a storm’s structure, how strong the winds are and how low the pressure is at the surface in the eye. This information is essential for improving hurricane forecasts and the best way to get these data is to fly an aircraft through the center of a hurricane using a variety of radar systems to analyze the storm whilst simultaneously releasing dropsondes.

Dropping measurements by the second

When a dropsonde is released by an aircraft it sends data back to the aircraft continuously through its 2,000-3,000 feet-per-minute descent.

Hurricane professionals or hurricane hunter aircraft often use the dropsonde in their missions. Here is how much data the dropsonde can transmit:

- Every half second: Transmits pressure, temperature, and humidity measurements

- Every quarter second: Transmits its 3D position using a GPS receiver (referred to as 4 Hz data)

- Every quarter second: The dropsonde also measures the wind from the GPS receiver because as the dropsonde is embedded in the wind field as it descends by parachute

Dropped into the eye wall of a very intense hurricane the dropsonde spirals around the center and can often splash to the opposite side of the eye as it follows the winds in the storm. The aircraft collects the data and transmits it in real-time via satellite to the National Hurricane Center. Computer models also receive the data, which researchers use to determine the structure of a storm and to forecast its intensity and trajectory.

* Built by Vaisala under license from UCAR, the Dropsonde NRD41, aircraft data system hardware, and software used by hurricane hunters are developed by the Earth Observing Laboratory of the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

The entire 2022 hurricane season as observed by the NOAA satellites.

Read more at:

- Atlantic hurricane season ends, impacts continue | World Meteorological Organization (wmo.int)

- Damaging 2022 Atlantic hurricane season draws to a close | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (noaa.gov)

- 2020 ATLANTIC SEASONAL HURRICANE FORECAST VERIFICATION (colostate.edu)